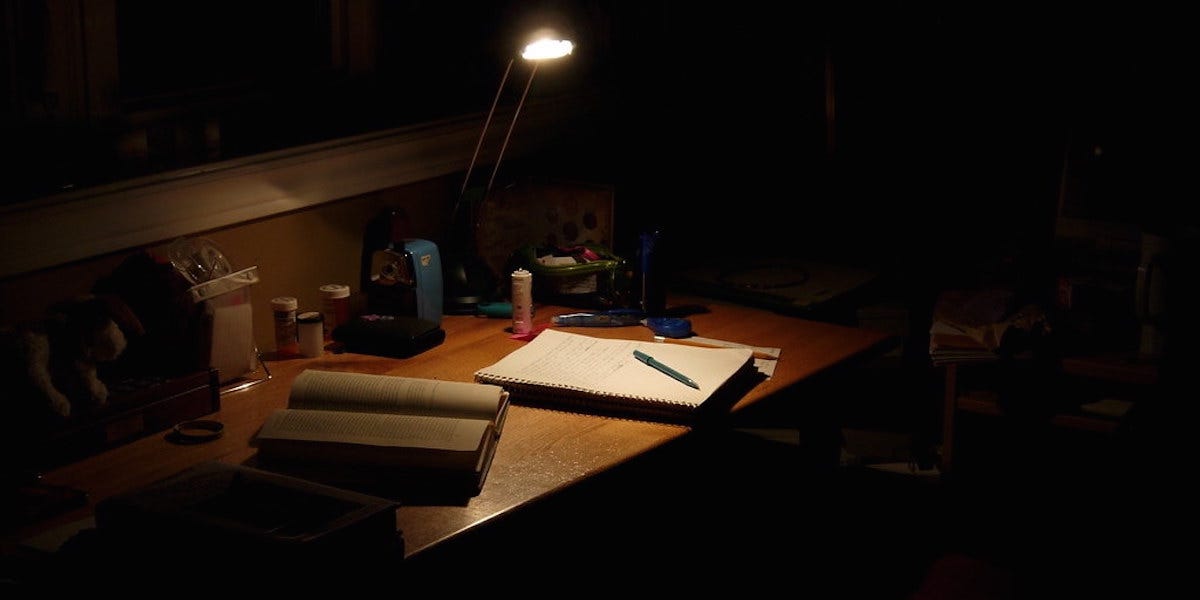

I finished a short story draft this morning before dawn. I don’t know if I’m going to post it here, but I’m definitely sending it to magazines once I edit it. That’s what it’s like to be a writer. You sit alone at a desk in the early morning or late into the night, making a world from the stuff in your head. You never know if you’re good. You never know if the responses you get (if any) are accurate or truthful. You’re completely alone in every way that matters. And, when you aren’t, you still are. Amateurs say “writing community” and the real artists give a little side-eye. Sure, sure, the writing community. That’s great. Now excuse me, I, uh, gotta be somewhere.

When you’re finished and the draft is as good as it’s going to get, you put it into the Submittable churn or email it to a magazine editor. If you’re a big deal or trying to pretend that you are, you send it to an agent or a manager, the beneficent industry parasites who are supposed to make everything easier but who can’t until you make it easier for yourself and don’t need them. Most of them don’t understand anything about sitting at the table in the dark.

And then your story, which is weirdly no longer connected to you, does its own thing out in the wild, cycling through the picayune innards of small-press publishing—the ugly Rube Goldberg literary digestion machine, glimpsed imperfectly at a distance and kind of stupid, mean, and silly all at at once. But by then you don’t care. You’re already on to another project.

A professor of mine once said, without early childhood loneliness, there’d be no one majoring in English. But I say, without lifelong loneliness, there’d be no one writing short stories or poems at 4:00 AM at the kitchen table. Or maybe I’ve got it backwards. Maybe without the stories, there wouldn’t be a cold, empty house. There wouldn’t be darkness and the need to imagine you are somewhere else. There wouldn’t be regret and the bitter absence of everyday joys that others take for granted. Because this is what you get, what everyone gets. This is the price for being able to make art.

Maybe I’m being melodramatic. Some days, I think so. On the worst days, not. Like when Vincent Hanna asks Neil McCauley in the legendary diner scene in Heat, “So you never wanted a regular type life, huh?” And Neil answers, “What the fuck is that? Barbecues and ball games?” And all Vincent can say, because it’s true, is “Yeah.”

Somebody asks me why I’ve been a wanderer all my life. Someone asks me what it is I actually do. And I have a variety of thought-stopping answers prepared. Because I don’t understand barbecues and ball games. I don’t understand normal life and day jobs, even though I’ve nearly always had one in which I wear a convincing man suit, function more or less effectively, and run a reasonable simulation of humanity.

A big part of the price is alienation, is becoming a weirdo, but that might be a chicken-egg thing. Would you have accepted this lifestyle if you weren’t already weird? When I was a kid, I spent most of my time alone, even when I was at school, especially when I was at school, making up stories. In college, the same. In law school, the same. In graduate school, the same. In fact, stories were what yanked me out of law school and full-on into the world of creative writing. Was I writing the stories or were the stories writing me?

James Baldwin said, “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world, but then you read.” And that also seems true. But then I think, would I be reading so much if I hadn’t already walked away from the barbecues and ball games? Shit, man, I didn’t even go in the stadium. I didn’t even get through the parking lot. A weird goth bus full of theater kids got me and I wound up smoking weed on a rooftop, asking is this where it’s at? And concluding, no, this isn’t. This is just another ball game. Where it’s at was back home in my room in my imagination. And now it’s at the kitchen table five days a week a few hours before I have to go interact with the general population.

Loneliness does strange and awful things. When we can’t share who we are or what we do in a meaningful way, something starts to rot and twist. And it never untwists. It just keeps twisting and rotting and twisting. You look at yourself one morning, at the shadows in your face, and ask, is this what I am? A creature of the night? You think, I’d rather be a night-blooming flower than a cockroach. But it’s all of a piece.

You’re a member of the class of beings that takes meaning in absence, in solitude, in the unnatural silence of the world asleep. But you’re not asleep. In fact, it’s the only time you’re fully awake. And so one comes to understand, to see oneself, in the figure of the moth, the vampire, the possum, the spider, the blossom at the end of a branch nodding in the wind, all the carnivora that wait for nightfall while the wide world pounds by overhead. The moon is their sun. And yours.

As I sit at my desk, like I did this morning and the morning before that and the morning before that, building artificial realities out of words, I often wonder what it’s like to lead a regular type life. “No such thing,” someone said to me recently, but he doesn’t know. He’s a weirdo, too.

I got up last week and the words wouldn’t come. So I went for a run and wound up walking through the neighborhood, hearing wind chimes, looking at yellow rectangles of distant windows. I watched black water twist under a bridge and felt the first drops of morning rain. No one was awake. No one looked out at the shape of a man standing still on a bridge in the dark, listening.